When Austin Hertzog, head sports editor of the Pottstown Mercury, enrolled at the University of Pittsburgh in the early 2000’s, the idea of being a journalist had seldom crossed his mind.

“I went to Pitt with the idea of becoming an orthodontist because that pays really well and it would be a great career,” Hertzog said at the start of a tell-all phone interview.

The young Lancaster County, PA native promptly abandoned his orthodontic aspirations after realizing, as many students do, that chemistry is incredibly difficult. He therefore set himself on a different path: writing about sports.

“I sat myself down and said ‘Well, I love sports and I do like to write. Why don’t I become a sportswriter?’” Hertzog said. “In retrospect, it was the most simple, stupid thing you could come up with but it gave me a real career goal in mind that set me on the right path with the right internships.”

With this decision to become a journalist, Hertzog would send his life on a wild journey that has supplied him with endless gratification and, unfortunately, endless anxiety and frustration. Hertzog has witnessed and lived a tragically underreported movement with disastrous effects on our democracy, society and basic ability to distinguish fact from fiction. He and many other small-town journalists in America are but cogs in a broken, dying machine: the machine that is local journalism.

As soon as Hertzog decided to commit to the idea of becoming a journalist, he switched his major, began to seek out internships, and found himself as a starry-eyed intern at The Pittsburgh Tribune Review, the city’s second-largest newspaper.

“The building at that time was positioned right in between Heinz Field and PNC Park, so I was faced with ‘the big time’ and it really gave me a goal in mind for continuing to pursue journalism.” Hertzog said.

When Hertzog graduated with a journalism degree, he went from being face-to-face with the ‘big time’ to being face-to-face with the realities of journalism. After working for a short time in his native Lancaster County, he was hired as the heir apparent to the late Don Seeley, then-sports editor at the Pottstown Mercury.

In the mid-2000’s, The Mercury, alongside most newspapers large and small in America, was still predominantly a print publication. Most papers were incredibly slow to transition to digital media, as they assumed that the internet and digital consumption of media was a temporary trend that would never oust the classic Sunday paper. As Hertzog laments, they could not have been more wrong.

“The newspaper powers that be were so short-sighted that they thought ‘The internet, it’s just a passing fad. People are always going to buy our newspaper so we’ll just throw it [online] for free because no one’s going to read it there.’” Hertzog said.

In a crucial misstep, most papers put nearly all of their product online for free for several years while the internet was still a burgeoning, unknown market. In doing this, they made the general public expect to receive news for free and stop buying printed newspapers, cutting off a major source of income that they have never really gotten back.

“By creating a free situation around your news content, you are now incentivizing people to not want to pay for what you are producing, which is totally insane for any business. If you don’t create value around your content, then you’ve lost your entire money making proposition.” Hertzog said.

This critical mistake at the dawn of the newest era of media has had lasting effects on the news industry. From top to bottom, news companies have been affected, with big fish like the New York Times even being forced into layoffs from dwindling profits.

For Hertzog and other minnows of the journalism world, the effect has been even more pronounced.

“When I became sports editor of The Mercury in 2013, my staff was going to be a total of six people. Most recently, throughout the back end of this fall, The Mercury’s sports staff has been just me. It’s changed my ability to do things and cover the area in as comprehensive a way as the previous standard has been,” Hertzog said. “It’s difficult to realign what your standard of excellence is when you don’t have the bandwidth to do what you previously were capable of, and it forces you to make tough decisions.”

Hertzog’s story is not an anomaly. Thousands of small papers around the country are experiencing similar challenges with understaffing and layoffs, hindering them from fully achieving their goal of providing news to communities. One common trait of most struggling newspapers stands out, however: corporate ownership.

The Mercury is a subsidiary of MediaNews Group, a Denver-based conglomerate that owns around 300 publications in the US. MediaNews Group, in turn, is owned by a hedge fund called Alden Global Capital. Most local papers can no longer survive independently, forcing them to be bought up by large hedge funds that further compromise their ability to function.

“There’s a cynical approach to ownership by the hedge funds in that they’re not actually trying to succeed at providing the news, they’re really just trying to buy up the properties and strip them of their assets to turn a huge profit margin. That’s part of why our staffing is so dire.” Hertzog said. “It’s almost like we’re being killed from within.”

Local news’ decline comes at the hands of uncaring corporate suits that would be perfectly content to liquidate their publications when profits dry up. The effect of this is a decline in the ability of local papers to cover events in their own community, leaving residents weaker in their knowledge of local happenings, politics, and corruption.

“The checks and balances of a community that local journalism provides such as informing people of what’s going on in a municipal meeting or in their school district or school board is where I see the biggest loss. Being a watchful eye on whether or not a local mayor gave himself a $300,000 raise, for example, makes journalists the protectors of truth and decency in the face of corruption. The death of local news is therefore a real concern from a community standpoint, a democracy standpoint, and for the health of a functioning civilization.” Hertzog said.

We see it so often nowadays. Local corruption, political extremism, and a general lack of respect and unity. In our own school board meetings, it has not been uncommon to see immature bickering and uncouth comments from board members and residents alike. This disunity and lack of decorum would certainly decrease if a healthy local publication were present to report on the events of the meeting and point out such offenses.

These events therefore beg the question: what happens next? If local journalism is to die off, we would most certainly be left with more corrupt, disunified municipalities. But will it actually die off? Hertzog, for one, is cautiously optimistic.

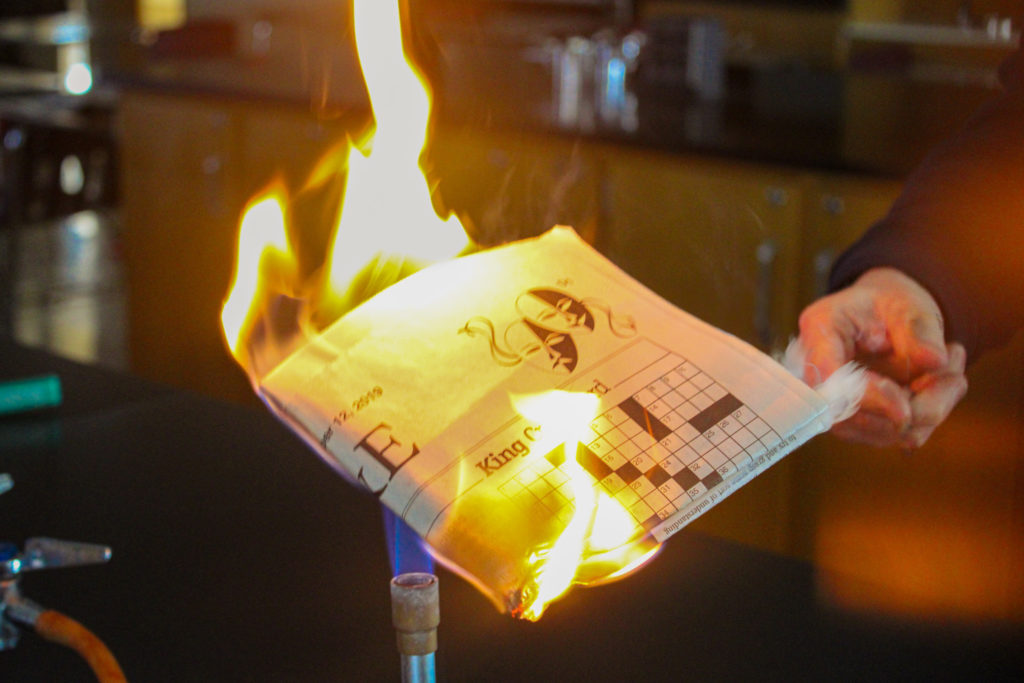

“My belief, for the last number of years, has been that, outside of these big newspapers, local journalism needs to burn to the ground and begin again. A bit like how newspapers worked at the start of our country, which is to say, persons in a community banding together to bring people the news. There of course needs to be funding for that, and it would probably have to happen in a nonprofit manner or from local businesses in order to monetize it and give journalists a living.” Hertzog said of where he thinks that journalism is headed in the not-too-distant future.

It is not only clear that local news is dying, but that local news is essential for the health of communities and democracies. We as a school and a community must therefore continue to support local journalists like Hertzog who work thankless hours with insulting wages to provide for the betterment of our area. As Hertzog and others around the country live each day with the thought that it may be their last in their current job, we must do all we can to keep local journalism alive.